In writer/director Wayne Groom’s recount of the making of Maslin Beach, he mentions that ‘in 1983, when I set down my future goals, my major goal was to produce, write and direct a feature film’. Reading this, I’m left with a burning question about what makes an aspirational filmmaker want to make a film? Is it the same energy that lives within hopeful writers who aim to have a completed novel to their name by the time they die? Is it the yearning to be remembered for something and to have made your mark on culture as a whole? Or, is it a matter of economics, hoping that their flick might earn them a tidy sum? Or is it a yearning desire to create a dialogue about the human condition?

For some, the passion to make a film comes as naturally as the torrent of imagination pouring out of their mind does, creating a work of brilliance in the process. For others, that filmmaking dream becomes their life passion, an enduring itch that simply won’t abate, yet that fever is left unmatched by a lack of artistic talent. No matter how many books you read, or seminars you attend, there is still an aspect of talent that needs to exist when it comes to filmmaking.

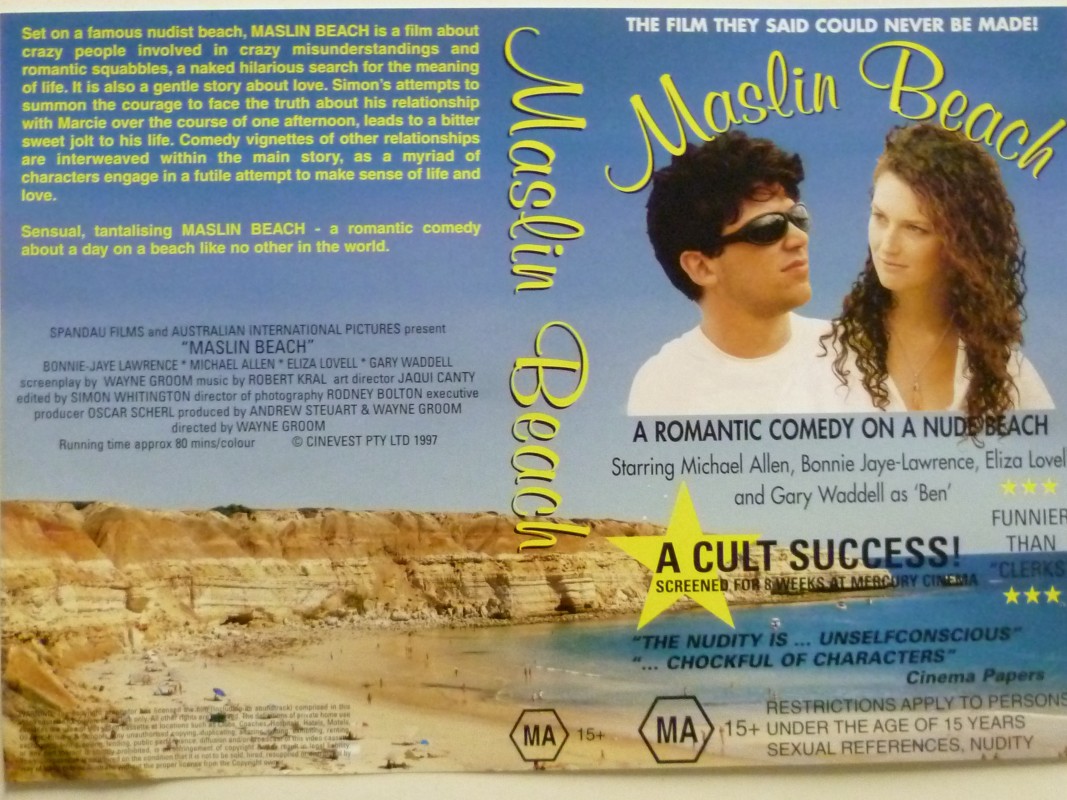

Groom goes on to clarify that once he completed Maslin Beach, quality aside, he had a desire to continue on making films. As Groom talks about his evolution from a producer into a director (‘long and arduous’), he mentions his need to move to America to learn about screenplay writing as the tools simply weren’t available in Australia. His query regarding the kernel of an idea he had about a man giving birth being taken, rewritten, and worked into the Arnie film Junior, points to a man driven by attention grabbing ideas, so much so that that act lead to him conjuring a subject that no studio would want to put their fingers on: a romantic comedy set on a nudist beach in South Australia.

Wayne Groom’s producing legacy kicked off with one of the landmark skin-flicks of the Aussie New Wave era, Centrespread. Arguably, one could see Maslin Beach as a continuation of the wide array of nudity-focused films that were plentiful in the seventies, waning in the eighties, and spotty in the nineties, with films like Sirens and Maslin Beach itself becoming late night successes on commercial TV, alongside popular shows like Sex/Life. Groom’s cinematic history alone points to why he might want to spin a story like this into film. If it was successful then, why is could it not be successful in the nineties? However, come the turn of the century, sex focused films in Australia had become a rarity, and those that did exist, have long drifted into obscurity, just like Maslin Beach did.

If we stick with the sex-focused subgenre, we find that most are out of print or digitally unavailable, with precious little writing actually existing about said films. John Curran’s Praise is nowhere to be found, Susie Porter’s excellent double whammy of Feeling Sexy and Better Than Sex have disappeared completely, and Ana Kokkinos’ Book of Revelation may as well not exist in the broader public consciousness. And worse, Paul Middleditch’s long forgotten (but no less brilliant) A Cold Summer lived only as theatrical film before disappearing into the pile of discarded Australian films, a fate that has unfortunately fallen upon far too many independent films.

Yet, quite peculiarly, Maslin Beach has a continued life online. Not on Netflix or Stan. Not on demand on Google Play or Apple TV. Nope. It lives on The West Australian website, alongside Wayne Groom’s entire filmography, as bizarre a place as any for a film of its calibre to find a home.

So, does Maslin Beach deserve the honour of being remembered?

First up, Wayne Groom’s filmography has extended long past his life goal of having produced, written, and directed a film, with his move into the world of documentaries being the work that he should be remembered for most.

Secondly, no matter the quality of a film, its presence in a countries cinematic history needs to be recorded and maintained. Even if it becomes a footnote, it is worthwhile documenting that it at least existed, even if it’s just as a curio of its time.

Now, if you believe what you read on the internet, then Maslin Beach is a cult classic comedy film. Or so we’re told from a 20th anniversary screening in Adelaide at the Mercury Cinema. Obnoxiously, I had presumed that Maslin Beach would likely only exist in the minds of a few men and women in Australia who were skin-starved in a pre-internet age and found some kind of pleasure in the wealth of t&a on display.

That deliberately glib statement does ignore the comfort that many find with naturalism. Maslin Beach strips the expected gratuitous aspect of the nudity from the film, actively desexualising the human body, allowing the vignettes that Groom has written to stand as singular stories where the people in them just happen to be naked. Additionally, the IMDb page does contain a few positive reviews that suggest folks found something more in the film than bouncing butts to keep them engaged.

Yet, my cynicism persists, as I find it hard to believe that anyone managed to get any kind of entertainment from the film itself, lurid or otherwise. Billed as a comedy, it’s extremely deficient in laughs, with its heavily telegraphed comedic moments failing to endear, instead carrying an air of misogyny to them that simply would not fly in today’s day and age, and certainly shouldn’t have been accepted in the nineties.

One sequence has a wealthy Italian jeweller propositioning a young woman, coercing her with money to perform sexual acts on him. She declines, stating that she’s looking for ‘true love’, he persists, she walks away, he’s smacked on the head by his angry wife. Elsewhere, a spiritually adrift hippie inspired by Henry Miller tries to find the meaning of life and the pinnacle of enlightenment in various places, notably between the legs of an unsuspecting woman who tells him to ‘rack off’ when she notices his ogling eyes staring directly into ‘the womb’. ‘You’re not going to find God in there’, she remarks, and he replies ‘no, but I think I found heaven’.

Elsewhere, another tale of sexual assault is played for laughs as a woman retells a bizarre story of her desperate ex-boyfriend who superglues himself to her during sex so they’ll never be apart. The extraordinary tale reaches increasingly unbelievable points til it hits is slightly grounded conclusion where she mentions that he was arrested under the sexual deviancy act in Tasmania and given fifteen years in prison. Darker still is her off the cuff comment that ‘it’d be life if it were a man he did it to’, pointing towards a horrifying level of gender imbalance in the justice system.

Finally, the less said about the incestuous relationship between a father and his daughter the better. In the above Q&A, Groom explains its presence as an homage to Anaïs Nin and Henry Miller, which by itself sounds fascinating, but within the context of Maslin Beach, it leaves a bad taste and is outwardly disturbing. Groom’s fascination with Miller is clear, making one wonder why he didn’t simply try and write a film about him instead?

What exists of the ‘plot’ is slight, with a middling through line of questioning lovers installed into the film to help secure funding. As figureheads of the varied cast, we follow Simon (Michael Allen) and Marcie (Eliza Lovell) through their day at the nudist beach, as they both come to realise that they’re not meant for each other. He’s a pathetic individual who knows he’s incompatible with his girlfriend, but persists with the relationship because they’ve been living together for two years and getting married is easier than breaking up. She reluctantly continues coming to the beach, never partaking in the clothes-free lifestyle, failing to appreciate why her boyfriend likes the lifestyle.

Groom may consider his work as being very European, with Eric Rohmer being a personal favourite, and the extremely comfortable and relaxed manner that the cast perform lending itself towards the blasé relationship with nudity in Europe, but the film is distinctly far removed from any European cinema. Aside from a tender moment of a naked operatic siren singing a song to the sea from the peak of the rocks, the closest Groom managed to bring Europe to Maslin Beach was with his experience of being naked on set with the crew, which lead to the following statement:

The film went very well mostly, although like Ingmar Bergman, I experienced diarrhoea every morning, a nervous reaction to stress I guess.

Maybe this is why he injected his script with such grand witticisms of life, such as ‘if you don’t fart, you don’t shit, and if you don’t shit, you die’.

But if it’s not European, then what is it?

Maslin Beach, for my estimation at least, is a culturally adrift film in the Australian cinematic landscape. It clearly exists, and yet, at the same time, its impact is so minimal that it very well may not exist at all. I’ve long championed the work of Aussie indie filmmakers who have managed to scrape a film together on fumes and duct tape, and yet, I look at a film like Maslin Beach and wonder how it managed to weather the annals of time. It surely can’t be on nudity alone. I lament the loss of so many smaller films that disappeared into nothing, forgotten and discarded, except for the occasional dedicated film festival programmer who saw it once, but never included it in their line-up.

Which again leaves the question, why did Wayne Groom decide to make this film? If it was simply so his idea couldn’t be stolen, then sure, he achieved that, but if it was to try and create a culturally significant film, then he missed the mark completely. There’s suggestions that producers felt that this could be part of the changing tide of Australian cinema, which is an understandable statement, but also a marginally misguided one given the Aussie film movement of the nineties was skewing towards being more commercially focused.

Profit wise, the continued TV rotation of the film in the nineties likely pushed it into the black. Where a film like Maslin Beach would have been met with packed theatres in the seventies, it falls flat as an occasionally lurid, consistently bland, nudie flick in the nineties. A winking saxophone wailing over the opening credits, playing like a showgirl flashing a little thigh, gives you an idea of the level of tact this film is operating with.

Maybe the most acidic and apt assessment of Maslin Beach comes from IMDb user jox, who had this to say:

What makes this film distinctly Australian is the fact that it is pointless … and only Australian Cinema, and other medium sized National Cinemas, could consider such a rash option.

In a short, blanket statement (that is admittedly supported by sound reasoning), this review chops down the film, and with it a plethora of like-minded Australian films. Just like many movies, the desire and dream of the filmmaker to make a film is not always enough to make going through the creative process worthwhile. It needs to have a purpose that makes the thousands or millions of dollars well spent, and to make the sweat and tears carry weight. Yet, just like countless other terrible films that forged through a creative process and reached completion, Maslin Beach, with its array of bare bodies, and $150k spent, exists in the world, relegated now to the role of being a pub quiz answer that nobody will get right.

Maybe highlighting a film like Maslin Beach in a review like this is counter-intuitive: pointing out its existence just to tear it down. But reasonably so, this film exists in Australian film history, and that alone deserves some kind of remembrance, even if it is just a final heaping of dirt on the grave of its memory.

Director: Wayne Groom

Cast: Michael Allen, Eliza Lovell, Bonnie-Jaye Lawrence

Writer: Wayne Groom