2020, as has been heavily documented, was a difficult year for cinema as a whole. Australian cinema in particular was hampered by shuttered cinemas and confusing release schedules, with many iconic films moving to streaming services to find their audience. Hopefully, with end of year lists like this one, I can guide you towards some of the great Australian films that might have skipped your attention or notice. Throughout 2020, I watched over sixty Australian films, both feature length and short, and while many impressed and lingered in my mind, these are the thirty Australian films from 2020 that I consider the best of the year.

Shannon Murphy’s global critical darling debut feature swept the 2020 AACTA Awards in a clean sweep, leaving everyone else in the dust. Murphy’s assured direction guided four of the finest modern performances in an Australian film, where young talent Elisa Scanlen and Toby Wallace were buoyed by the helpful ballast that was seasoned veterans Essie Davis and Ben Mendelsohn. While this cancer drama does tread a familiar path, it manages to do so in a manner that secures a powerful gutpunch of an ending that is hard to shake. Mendo in a moustache on a beach has never been a more moving sight.

Read the Babyteeth review here.

It wouldn’t be a year of Aussie cinema without a Kriv Stenders release. This bloke never sleeps. Continually bouncing between documentaries, television, and feature films, Kriv has continually set the benchmark with a sustained output of great work. Kriv’s continued interest in Australian music legends carries on with the Joy McKean and Slim Dusty doco, Slim & I. As a wonderfully vibrant glimpse into the extensive history of the Australian Country music legend, the true joy of this doco comes from hearing the equally iconic Joy McKean talk about her role in Slim’s path to stardom. Additionally, the awe and respect from fellow Aussie artists is purely tangible, making this more than just a fan-friendly flick.

Read the Slim & I review here.

Newcomer director Maziar Lahooti transforms his acidic short film Abraxas into a pitch-black comedy about Australia’s treatment of refugees. With a gloriously unhinged performance from the ever-excellent Ryan Corr, Below slaps you in the face continually with its defiantly bitter stance on modern Australia and its actively cruel treatment of asylum seekers. As Corr’s greedy, yet resourceful, Dougie attempts to dig himself out of his self-inflicted debt burden, he manages to opportunistically inflict further trauma on the refugee population he’s employed to guard and monitor by subjecting them to horrifying bare-fisted cage fights in the desert. As bleak as it sounds, Below unveils each scene with a knowing wink, highlighting the absurdly evil undercurrent of Australia’s ‘border protection’ policy, in turn asking, who exactly is being protected?

Read the Below review here.

Alana Hicks bright and funny short film Chicken explodes with the lived-in experience of everyday prejudice that occurs incidentally for two PNG immigrants, Barbara (Mariah Alone), and her mother Rita (Wendy P. Mocke). Barbara just wants to watch The Simpsons, but when she hears that her mother has been short changed at the supermarket, it’s up to her to stand down the White check out people, Dion (Mia Evans Rorris) and Shelley (Greta Lee Jackson), and get back the money her mum lost. Hicks accentuates a familiar, everyday occurrence with a highlighted act of miscommunication, spotlighting the cultural barriers that White Australians inadvertently put up through deeply ingrained prejudices. With spirit-filled performances from the entire cast, and a witty script to boot, Chicken acts as the proud announcement of Alana Hicks on the Australian cultural landscape. Welcome.

Every moment that director Robert Woods spends building up towards the gory finale of writer Tyler Jacob Jones genre-informed script for the indie-film An Ideal Host, is another moment that highlights the cinematic prowess that these two young filmmakers have. Here, a celebratory dinner party is rudely interrupted by an unexpected guest that turns the whole night on its head and disrupts a local town completely. Woods and Jones pick up from where the microbudget masters like Peter Jackson, the Spierig brothers, and the Roache-Turner brothers left off, with a not-at-all-questionable fascination with practical gore and effects paired up with a giddy-like level of comedy, making An Ideal Host the kind of film that’ll be discovered in years to come and be rightly celebrated as a horror-comedy delight. Go into this one blind if you can and you’ll be greatly rewarded with a genuine indie treat.

Read the An Ideal Host review here.

This brilliant short has double-threat writer/actor Tina Fielding’s Courtney, a thirty-something Down syndrome woman, escaping the country and legging it to Perth where she’s going to make something of her life. On the way, she encounters Diamond (Gary Cooper), an ageing drag queen who encourages Courtney to celebrate her life as her glitter-adorned karaoke singer: Sparkles. Tina Fielding’s memorable performance in this colourful WA made short film should be enough to secure her a feature film in the future. Heck, I’d be lining up day one to see director Jacqueline Pelczar guide another one of Fielding’s script to the big screen if it meant seeing the wonderful Fielding act again. This bite of delight is another reason why Aussie short films deserve to be held on the same pedestal as the great features and docos we produce. More please.

Aussie animation regularly shows its best side in the short film format, and director duo Sara Hirner and Rosemary Vasquez-Brown’s brazen and proudly vulgar short GNT stands head and shoulders above the rest this year. The proof is in the pudding with the directors being rewarded with the prestigious Yoram Gross Award at the 2020 Sydney Film Festival. GNT is four minutes of feminine modernity wrapped up in a body conscious vibe that is emphatically unique, especially in its masterfully mockery and celebration of pop culture, social media, friendships and the dramas that flourish within them, feminine hygiene, and more. GNT acts as an amuse-bouche for whatever Hirner and Vasquez-Brown do next. Realistically, if Stan. or Netflix were looking for the next big animated hit, then they should look no further than these two directors who clearly have a lot they want to say, and dammit, they deserve the biggest platform to do so.

Watch the GNT trailer.

Roderick MacKay’s Goldfields Western, The Furnace, is in a film that gradually unveils itself to be a quiet and considered trek across the sundrenched outback, where cameleers keep trade routes alive and corpses of fallen foes linger in the dirt, awaiting the hungry mouths of dingoes in the night. Muck stricken Mal (David Wenham) exudes the desperate aura of a grounded grifter, stringing along cameleer Hanif (Ahmad Malek) as they both make way to a hidden furnace where they can smelt £3000’s worth of stolen Queens gold. As the law breaths down their neck, and the land threatens to claim their souls, Mal and Hanif witness an Australia that denies anyone that isn’t White a place to call home. The Furnace contemplates a country founded on oppression, and at its conclusion, the viewer is left assured that Roderick MacKay’s feature debut is a welcome, confident arrival.

Read The Furnace review here.

Ailís Logan writes and stars in Wine Lake, a tender and empathetic short film about a homeless alcoholic, Peg (Logan), and their encounter with an artistic backpacker, Conor (Aaron Tsindos), at a laundromat. Meeting as strangers, and connecting over a shared Irish heritage, the two soon discover that they have more in common than a unique accent and an appreciation of art. Over the span of nine minutes, the enormity of a lifetime lost is made apparent, with the reality of adoption processes in Ireland being made devoutly clear. Direction from Platon Theodoris is assured and confident, allowing the humanity between Peg and Conor to become the focal point, encouraging a naturalistic approach to the storytelling that will leave you moved by the end. On paper, a film like Wine Lake may seem slight, but it’s with stories like this that the power and strength of humanity is reinforced.

Watch the Wine Lake trailer here.

Director Ben Lawrence deftly follows in his fathers footsteps with his first fiction film, Hearts and Bones. Having already made a name for himself with the haunting documentary, Ghosthunter, Lawrence turns his gaze to a morally complex narrative of refugee, Sebastian (Andrew Luri), and war photographer, Dan (Hugo Weaving), who has captured a secret that may upturn Sebastian’s life. Almost exclusively making Australian films now, Weaving continues to remind audiences why he is one of our finest actors, with his role in Hearts and Bones being an arguable career-defining achievement. Lawrence hits for the fences with this powerful drama, and while not all of them are sixes, he does manage to leave the viewer with one of the most audacious and jaw-dropping conclusions in an Australian film ever that criticises Australia’s record with asylum seekers in a masterful manner. If this is the note that Ben Lawrence wants to hit for his career going forward, then we’ve got some fascinating work to look forward to.

Read the interview with Hugo Weaving here.

Top Gear mastermind Owen Trevor made his feature debut with the West Aussie family friendly flick, Go! Written by Steve Worland, who improves upon the already impressive work he did with the Robert Connolly’s top tier kids film, Paper Planes, Go! kicks off one of the repeating aspects of 2020 Aussie films: stellar kid performances. Knocking it out of the park is the trio of performances from William Lodder, Anastasia Bampos, and Darius Amarfio Jefferson, who together play a plucky group of kids who construct a go kart and intend to triumph over the local karting giant. Following the sport film formula intimately, Go! makes its mark on the genre with zippy racing sequences, charming dialogue, and a vitality rich spirit that makes this family friendly film a must see. It’s one I’ve certainly found myself revisiting throughout the year to joy filled delight, especially thanks to Richard Roxburgh’s gruff supporting turn.

Read the Go! review here.

Ili Baré’s timely documentary immerses the viewer in a world that proposes empowerment, equality, and a positive future for women in science focused areas with entrepreneur Fabian Dattner leading 76 women scientists on ‘the trip of a lifetime'. What instead eventuates on this intimate journey to Antarctica with a vessel full of optimistic women is the cruelly natural realisation of the inevitability of inequality. With the hope of change and the power to instigate a difference at their fingertips, this diverse group of women grow to realise that under Fabian's tutor, the concept of women empowered leadership is a fallacy, and as such, any opposing voices or consideration for the mental health struggles are equally discarded and neglected. The Leadership paints an equally optimistic view of the fight for equality, alongside a damning condemnation of what it means to be a leader. Does leadership mean following a prescriptive template for success? Or does empowered leadership only come with the support and guidance of your peers? Where Bare takes the audience is unexpected, and that's where the brilliance of The Leadership lies: in how it creates varied discussion points on a hotbed current topic: equality.

I look forward to mentioning the next entries in the 100% Wolf series in future Best of Australian film lists, because gosh, if the first film is any proof, we’re in for an absolute treat. Before I get ahead of myself, first time round we've got youngster Freddy Lupin as a werewolf pack leader in waiting. On the night of his first howling, instead of turning into a raging wolf, he turns into a poodle. Following on from the hallowed footsteps of animation titan Yoram Gross, 100% Wolf is positively charming and full of rampant PG-level frights and comedy. This is a world class flick that should help remind audiences that while infrequent, Australia does make some truly great animated films.

Read the 100% Wolf review here.

Way back before the pandemic locked down Perth, the WA Made Film Festival kicked off a three day celebration of West Aussie films. Over that weekend I got to see the thriving imagination of WA filmmakers writ large, with great features, and even better short films. Ringing loudly in my mind since then is Aisling Rose McGrogan’s one person short, Loveless. Made completely by herself, this short has Aisling play a housewife and her partner, shown as a moustachioed Hawaiian shirt wearing dude (again, played by Aisling). Set at a dinner table, the two talk about their relationship with each other in a dialogue driven scene that left me laughing harder than I did in any other film in 2020.

As Aisling plays opposite herself in her own kitchen, she applies a YouTube taught DIY mindset to the tricky splitscreen technique that often seen in films or shows like Adaptation or Living With Yourself. The creative ingenuity and fascination with cinema that Aisling exhibits is utterly brilliant, with a distinct desire to make the screen her own. Part of the reason why Loveless has stuck with me for so long is this film comes from someone so keenly intrigued, interested, excited and impassioned with the artform of cinema that their excitement with the format is purely tangible. Loveless came for me at a time when I was feeling despondent with the realm of cinema, and worried about the increasing lack of creative spirit with films across the board – both locally and internationally – and yet, here is a one person made short that is so filled joy and so in awe of the machinations of storytelling and cinema that I can't help but hold it up high as a hopeful sign of things to come.

I’m not saying that Aisling is going to save cinema, but rather, I want to circle out how downright nice it is to see someone who so clearly enjoys making cinema that you, as the viewer, can’t help but be enraptured by their resulting output.

Read about the WA Made Film Festival here.

Paul Ireland arrived on the Aussie film scene in 2015 with Pawno, a microbudget feature made with proud confidence alongside mate Damian Hill. Their follow up, Measure for Measure is a Melbourne set Shakespeare adaptation, scripted by Hill and featuring a jam-packed cast of Aussie titans. Dame's script swings for the fences and brings the strine to ol' Shakey with great confidence, in turn giving Hugo Weaving a villainous lead to sink his teeth into to excellently counteract against the sympathetic Dan in Heart and Bones. Where Pawno highlighted two stars on the rise, Measure for Measure cements Megan Smart as a force to be reckoned with. Her performance as Jaiwara imbues the film with the emotional undercurrent it requires, with Smart showing accents of strength and vulnerability, often in the same scene. Supporting turns from Mark Leonard Winter, Daniel Henshall and Fayssal Bazzi all help make each act of violence carry its intended weight. Given this is Shakespeare, Ireland plays to the tragedy of the piece masterfully, honouring the late Dame Hill in the process in the finest way possible. Measure for Measure triumphs in a grand manner, it reaches for the skies and has the spirit to get there.

Laura Gordon’s performance in Undertow as a wife of a football icon is one of the modern great Australian performances. This is a full bodied, lived-in role that gives a voice to the voiceless and honours the countless women of the world who live with the trauma of miscarriages. While Gordon's Claire is a character steeped in tragedy, she is a defiantly non-tragic figure, walking through her narrative of doubt and investigation into her husband who may or may not be having an affair with Olivia DeJonge's youthful Angie. An unexpected duality of motherhood and toxic tenderness arises when Claire and Angie start to engage with one another, threatening Angie and Claire’s mental states. Writer/director Miranda Nation organically weaves this narrative thread into one about the increasing misogyny in Australian sports in an intimate manner that informs the deeply investigated script, making Undertow a timely film that addresses inequality and violence in Australian sports.

Read the Undertow review here.

Camp Cope’s fury driven song The Opener wraps up with a line that echoes throughout the minds all listeners: yeah, just get a female opener, that’ll fill the quota. That tokenistic rhetoric is a genuine reality for many women musicians around the globe, giving the week-long music camp Girls Rock! Melbourne a suitable challenge to tackle head on. And gosh do they manage to knock that quota-mindset off its feet. No Time for Quiet follows the first year's camp throughout their journey and beyond, highlighting the camps consideration towards gender equality, mental health, community building and empowerment. As we follow a few main subjects, we get to see how the music community at the camp helps them process mental health struggles, or overcome social battles. Yet, we also witness what happens when the support network established over the week disappears, once again highlighting the need for continued community. No Time for Quiet is at times a raucous and loud film, and at others, it’s counterbalanced by a gentle and touching level of care and understanding. At its conclusion, you’re left hoping that every city gets their own Girls Rock! camp. The tangible enthusiasm of the young kids attending the camp makes No Time for Quiet a thrilling and exciting watch that reminds how bloody exciting making and listening to music can be.

Samuel Van Grinsven’s queer drama, Sequin in a Blue Room, suffered a similar fate as other Aussie queer dramas, where, like Teenage Kicks or Downriver, it had a slow, staggered release. As such, this stunning film may have appeared on ‘Best of 2019’ lists, but for me, the first time I got to see Conor Leach’s stunning feature film debut was in 2020, and gosh am I glad I did. Deceptively slight on plot, Sequin in a Blue Room follows Sequin (Leach), a sixteen-year-old boy navigating the blossoming world of queer sex and romance. Samuel Van Grinsven frames Sequin’s narrative in chapters titled after each apartment that he visits every time he encounters a new lover, and doing so, he drenches the film in a visually stylistic manner that helps set it apart from other queer dramas. As queer narratives are so often focused around the romance angle of a relationship, it’s refreshing to see a youthful figure leaning into his craving for the carnal side of romance, and Leach’s central performance makes this journey a positively entrancing and mesmerising one. The promise of artistic quality from Van Grinsven and Leach here suggests that Australia now has a new important voice in queer cinema to celebrate.

Read the Sequin in a Blue Room review here.

It feels fortuitous that Sequin in a Blue Room would sit comfortably next to the sex-positive documentary Morgana on this list. Both celebrate the human form and both uncritically portray the sexual desires of their central subjects. Here, directors Josie Hess and Isabel Peppard document the life of Morgana Muses, a housewife who reinvents herself in her 50s as a pornographer who uses the genre of film to address the trauma of a loveless marriage and the mental health struggles that come with it. There’s a deep relatability to Morgana’s journey, with a comfortable universality to the place of difficulty that Morgana finds herself in. I look at Morgana in the same manner as another documentary from 2020, Keyboard Fantasies, where the younger generation of pornographers look up to their older counterparts as champions and figures that need support, and I see how Hess and Peppard equally support their subject throughout the filming of the documentary, recognising the pressure that Morgana lives with across the five years of filming, making Morgana an act of nurturing and care. Through the support of crowdfunding, a documentary like Morgana can exist in the world, where it will hopefully find folks who were in similar situations to Morgana, who might see a glimmer of hope in the darkness of their lives and take the turn towards a more positive existence.

The celebrity of Captain Cook is deftly dismantled by the cheekiness of Steven Oliver in the refreshing documentary, Looky Looky, Here Comes Cooky. Blending White history with Indigenous history meticulously, Oliver educates and entertains by presenting the arrival of the Cook legacy from a First Nations perspective. As he does so, he proposes an idea: create a new songline for 21st century Australia. With the help of Trials, Mo’Ju, Alice Skye, Mau Power, Fred Leone, Birdz, and the icon that is Kev Carmody, Oliver weaves a modern songline that addresses Cook’s impact on Australia and clarifies his history in an amusing, yet grounded perspective. Paired with stunning visuals of the scenic Eastern coast of Australia, Oliver bounces off the screen in a manner that is positively entrancing. Oliver has commented about the film, saying: ‘If you take parts of several truths and add them together, usually the truth is in there somewhere. It’s making people agree on it that’s the hard part.’ After watching Looky Looky, Here Comes Cooky, you’ll be reassessing Cook’s legacy and be left wanting Oliver to narrate every documentary about Australian history going forward.

In a year where grand spectacle cinema was missing from our lives, it became a small surprise that a Perth made short film managed to fill the gap that was left. Enter Antony Webb’s visionary film, Carmentis. Ben Mortley plays Mac, a miner stranded on a remote planet, relying on the assistance of his AI guided suit and the memories of home to get him to safety. Mortley’s performance is positively entrancing, with the tangible reality of needing to overcome physical and mental obstacles on his journey to help. Yet, what elevates Carmentis above being a routine emotional journey is Webb’s keen appreciation and understanding of the sci-fi genre, and his awareness for the need to employ an accent of awe into the mix. Visually, Carmentis is intoxicating and breathtaking, with images that linger in your mind for months to come. As with all the other short films on this list, Carmentis excels by understanding the restrictions of a short film and playing to the strengths of the format rather than pushing to squeeze a feature into a shorter runtime. As such, I’m still left moved by the narrative Webb and his team have weaved, so much so that I simply cannot wait to hear the news of a feature film from Webb.

Read the Carmentis review here.

With concert halls left empty in 2020, director Tim Cole stood up and delivered a documentary that filled our homes with music. Small Island, Big Song showcases 16 Island nations from the Pacific and Indian Oceans, from Madagascar to the Torres Strait, who together sing songs about their combined history along the ocean highway they call home, as well as the impact of climate change on their lands. Full of picture postcard visuals and smiling faces, Small Island, Big Song is the holiday journey you couldn’t go on in 2020. The music is itself a warm embrace that soaks you in the beauty of the world and opens your eyes to a commonly perceived hidden part of the world. Tim Cole’s masterful direction helps pull these different song threads together, with music carrying from one nation to another, where a singer on the shore fills the air with their harmony, all the while a guitarist strums in a distant land, making a new songline that unites these islands together. Like many of the documentaries on this list, Small Island, Big Song was a hidden gem from the Melbourne Documentary Film Festival, but its relative obscurity should make the journey to find it all the more satisfying. A genuine delight of a film.

Listen to the interview with director Tim Cole here.

Leaving Allen Street is currently scheduled to air on ABC TV Plus on Wednesday, 10 February at 8:45pm (and on ABC Australia/International on Sunday, 31 January at 5pm for anyone overseas).

Another MDFF entry is the proudly empathetic documentary Leaving Allen Street. Director Katrina Channells and the team at OC Connections have managed to craft a deeply valuable documentary about the importance of encouraging and supporting the integration of intellectually disabled people into society, all the while enabling an autonomy in their lives that they have long been denied. As Nadine wrote in her review, this is a film that ‘shows just how joyous ... coming together is’, and sure enough, Leaving Allen Street shows how important and valuable community is. Channells and co. ensure to highlight the history of The Oakleigh Centre, an institution where many intellectually disabled people were placed, and which was, for a long time, considered ‘best practice’, as they depict the movement of its occupants into new, custom built facilities that will allow them to live lives for themselves and each other. This is far from being ‘inspiration porn’, but is instead a celebration of humanity and the people who society has long deemed necessary to lock away. Like plenty of the films on this list, I’m unsure what the availability of Leaving Allen Street will be going forward, but I do hope that it becomes available for many soon so that people can absorb this utterly heart-warming tale. It’s the life-affirming film we need right now.

Read the Leaving Allen Street review here.

From the uplifting to the horrifying, Leigh Whannell continues to redefine the genre of horror with his masterful fearfest, The Invisible Man. Elisabeth Moss grounds this tale of gaslighting and domestic violence, and in the process, confirms that this is one of the modern great horror films. New South Wales steps in for Somewhere, America, creating an otherworldy experience which feels American, but not quiet. Everything seems just a little askew and unnatural, a point that amplifies the mental anguish that Moss’s Cecilia lives with. Powerful visual effects and heart-stopping jump scares also accentuate the realisation that while, on paper, Cecilia’s ex is apparently dead, his presence is still felt everywhere Cecilia goes. Naturally, he is still there in her life, disrupting it violently and traumatically, and giving her every reason to fear his existence. Whannell writes and directs The Invisible Man in a considerate manner, never exploiting the real world horror of domestic violence for cheap thrills, instead allowing the amplified terror to reinforce why we need to listen to women and instigate safe changes for women around the globe.

Read The Invisible Man review here.

As I mentioned in my review for director Christiaan Van Vuuren’s genuinely surprising comedy, A Sunburnt Christmas is an instant Aussie Christmas classic. This is in no short part to the great lead performance from the always-reliable Daniel Henshall, who is comfortably supported by one of the greatest performances of the year: Lena Nankivell’s Daisy. Daisy, and her siblings Tom (Eadan McGuinness) and Hazel (Tatiana Goode), help keep their home Hattersley Homestead alive, while their mother (Ling Cooper Tang) mourns the loss of her partner. While all of the performances are truly brilliant, it’s Lena Nankivell who positively steals the film, embracing the joy that comes with Christmastime and embodying the loving spirit that the season is known for. In a year that’s defined by great child performances, it’s Lena’s supporting turn here that takes the cake as the best of the bunch.

Read the A Sunburnt Christmas review here.

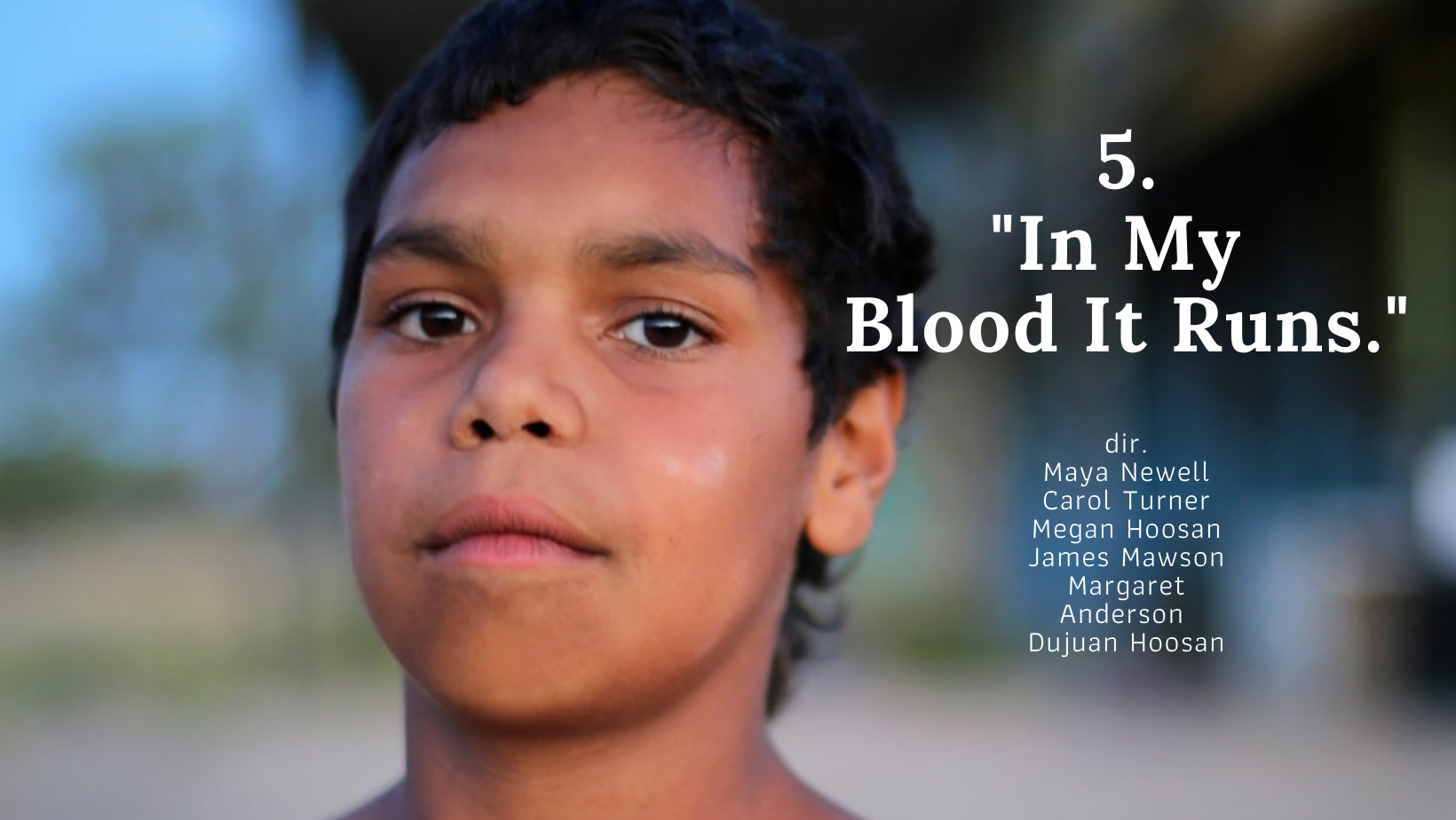

While Maya Newell’s name sits as the ‘director’ on IMDb for In My Blood it Runs, it’s worthwhile noting that in the credits of the film Newell highlights the collaborative nature of the film itself, with Carol Turner, Megan Hoosan, James Mawson, Margaret Anderson, and subject Dujuan Hoosan being collaborative directors. This is purely logical given the narrative of this stunning documentaries subject, Dujuan, a young Arrernte/Garrwa boy who is forced to navigate the Western culture driven school system that denies a place for Indigenous education. In My Blood it Runs highlights the need for a collaborative approach when it comes to education, a point accentuated when Dujuan and his classmates are taught a whitewashed history of Australia that celebrates the invaders of the land and holds Captain Cook up as a saint. After the film wrapped, Dujuan addressed the United Nations Human Right Council and talked about the need for Aboriginal-led education models around the globe. In My Blood it Runs shows the need for change in Australia and the power of community lead changes and decisions. It should force politicians to sit up and enact change immediately, but as has clearly been shown with a toxic welfare card system that only benefits a rich mining magnate, our current government has little sympathy for the traditional custodians of the land. I hope that any future leaders who do see this film keep it in their mind when making decisions about the changes upon this land we call Australia, because the people Western society stole it from deserve so much more than what they currently receive.

Read the In My Blood it Runs review here.

Justin Kurzel’s barnstorming, spit-in-the-face-of-masculinity depiction of the Ned Kelly legacy just about works as the defining cinematic portrayal of the famed bushranger. George MacKay deftly handles the Aussie accent as the beardless Ned, one of the first signs that Kurzel is chucking the Kelly-rulebook into the fire and forcing the audience to question what the point of a legend like Kelly is. For Ned faithfuls, this perceived slander against their cop-shooting icon was too much to weather, with many turning against the film for its depiction of the Kelly gang as a dress wearing mob of mad men shooting the heavens down during the pitch-black night. Kurzel’s defiant attack on the myth of Ned makes for an entrancing experience, especially with a seizure-warning laden climax that feels like a shootout at a rave, which makes way for a silent Ned being hung in gallows with no audience. At its close, True History of the Kelly Gang shows a politician forcing the fateful line - ‘such is life’ - into Ned’s legacy, hammering home the point that with myths like Ned’s, the truth no longer exists. As Travis Johnson wrote in his review: ‘the key to True History of the Kelly Gang is understanding that this tension between history, artistry, and ideology is the entire fucking point.’

Read the True History of the Kelly Gang review here.

One of the greatest aspects of Jeremy Sims masterful Mount Barker set remake of the Icelandic film, Rams, is that not once during its powerful two-hour runtime do you ever question why Sam Neill’s disease fearing sheep farmer, Colin, doesn’t relinquish the ovine industry and shift across to the more iconic and notable chicken industry that has put the town on the map. Instead, you’re left so entranced and engaged with Neill’s career best performance, alongside his onscreen brother Les (a shaggy Michael Caton), that you don’t have a moment to consider the avian industry. Rams is easily one of the timeliest and defining Australian films of 2020, given it has a plot that grapples with an unstoppable disease, bushfires, isolation, and mental illness. Promoted as a comedy, Rams is anything but a laugh-fest, with the gravity of the situation that warring brothers Colin and Les find themselves in being explored to its empathetic natural conclusion. With Last Cab to Darwin and Rams, Jeremy Sims has created two defining odes to the ageing worker experience in Australia, respectfully honouring the hard-working souls of the land who toil day and night in solitude, with only their minds to keep them company. Rams managed to weather the pandemic and stood up high as a box office success, giving me a little bit of faith that the audience for great Australian films is still hungry for more.

Out of all the films released in 2020, H is for Happiness is the one I rewatched the most. After seeing it for the first time at Cinefest Oz in 2019, leaving the screening with tears streaming down my face from laughing and smiling so hard, I caught it again in its theatrical release, and have found the exploits of Candice Phee (a luminous Daisy Axon) to be a great comfort over a rather distressing year. Her optimism and hope to find a little bit of happiness for her family helped give me some kind of strength to carry on and push forward. I wrote in my review how I wish that I had this film growing up, and while that’s still true, I’m just as happy that I have this film in my life as an adult. Family friendly entertainment is often overlooked in yearend lists, especially if it’s not ‘adult’ enough, but I do hope that the optimism and positivity that Candice, and her friend Douglas Benson from Another Dimension (the delightful Wesley Patton), exude as they walk on stage as Dolly Parton and Kenny Rogers, singing Islands in the Stream, rubs off on you and gives you a smile to make your day a little brighter.

Read the H is for Happiness review here.

Natalie Erika James assured debut, Relic, should comfortable posit her next to Jennifer Kent as one of the great modern Australia directors on the rise. With this horror of the soul, James respectfully depicts the movements of a ceasing mind, ground down to a halt by the machinations of dementia. Emily Mortimer’s cautious Kay returns home with her daughter Sam (Bella Heathcote) to seek out her missing mother, Edna (Robyn Nevin). Together, Kay and Sam discover Edna’s house in disarray, post-it notes stuck to different accoutrements and furniture as beacons in the night for Edna to discover in a moment of cognisance. As Kay helps restore some kind of order in Edna’s home, she grows to realise that there is a darkness in Edna’s body that is stripping her mother away from her. Outwardly horrific, Relic remains grounded in empathy and reality, leading to a conclusion that swerves when you expected it to duck, and by doing so, leaves you emotionally shattered. Out of all the Australian films of 2020, even H is for Happiness that brings so much joy to my life, it’s Relic that I return to in my mind continually, thinking of how delicately and tenderly James and co-writer Christian White have managed to depict such a relatable and humane experience through the genre of horror. In short, Relic is a masterpiece.

Read the Relic review here.