Before we dig into 2023, let’s take a short jump back to October 2021. Stage 1 of the Australian Feature Film Summit (AFFS) was taking place online, providing producers, distributors, exhibitors, and creatives the chance to review the performance of Australian films over the past year and to see what opportunities lay ahead for filmmakers. As speakers splashed graphs and stats and lists of box office information on the screen, the chat room was humming with one pertinent question:

Where was the support for Australian genre films?

Commenters chimed in demanding that the focus shift from drama to globally popular genres like horror and sci-fi as a way of broadening the appeal for Australian films[i]. These genres are well-serviced by film festivals like Fantastic Fest and Sundance where audiences are less risk-averse and more eager to dive straight into the unknown, allowing them to build up hype before being unleashed on the greater filmgoing public at large. I can’t say for sure whether it was part of those discussions at AFFS that helped spur on the Aussie genre film revival of 2023, but I’d like to think that that’s where the kernel of the idea was planted.

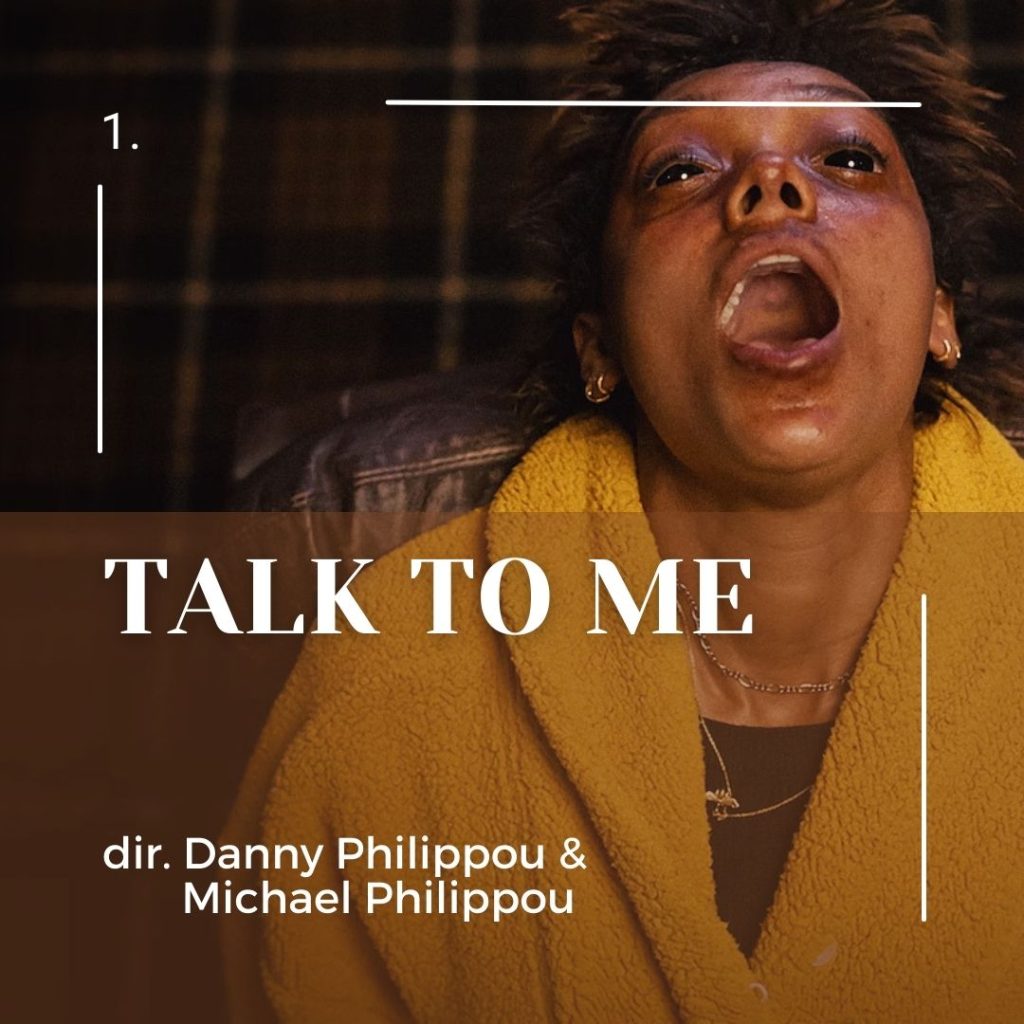

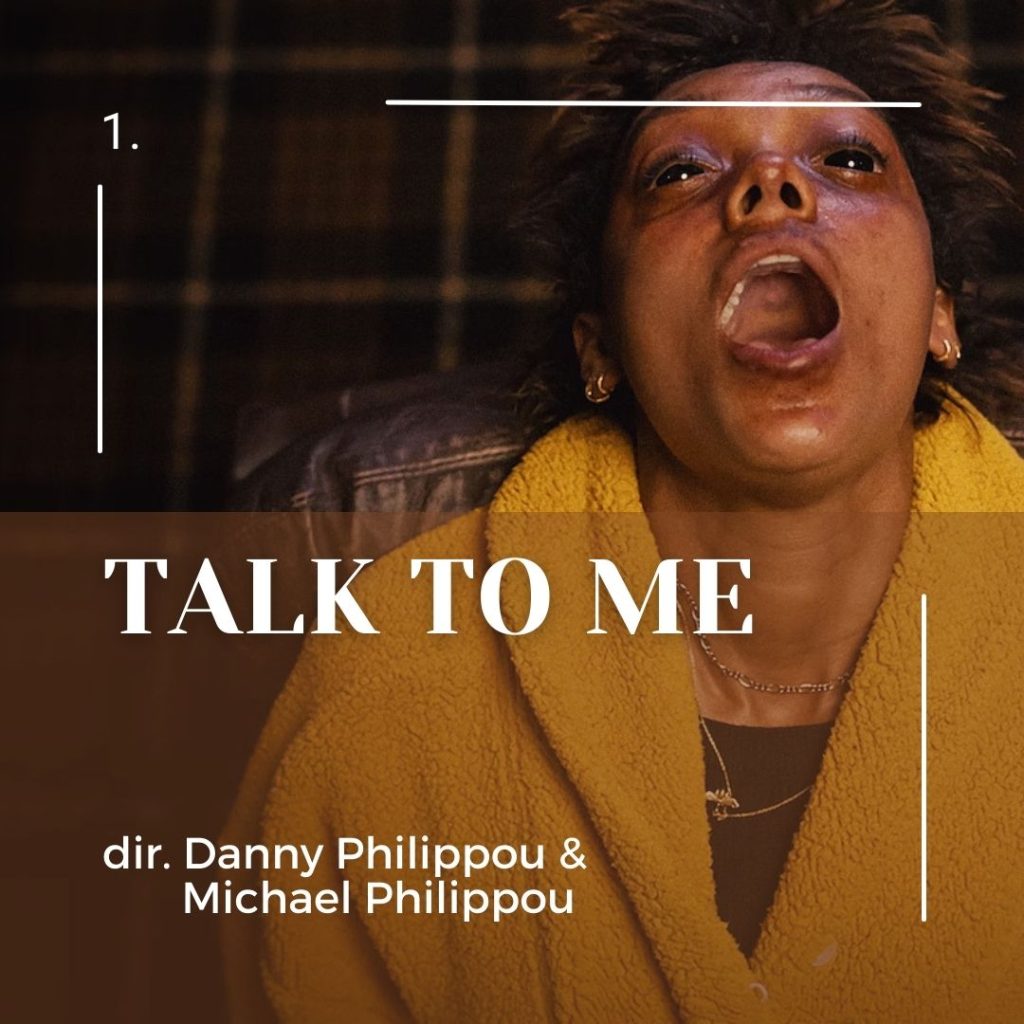

Case in point: Daina Reid’s Run Rabbit Run and the Philippou brothers Talk to Me which both debuted at the 2023 Sundance Film Festival, forming a posse of possession flicks with the Cairnes brothers Late Night with the Devil and Nick Kozakis’ Godless: The Eastfield Exorcism, and helping usher in a year of nail-biting tension (Matthew Holmes’ The Cost), unsettling sci-fi (Matt Vesely’s Monolith), and maniacal masculinity (Jack Clark & Jim Weir’s Birdeater). Aussie horror and sci-fi were no longer fringe fare, but genuine audience-pulling events.

Part of the appeal of these Aussie flicks comes from the way that distributors and filmmakers have equally harnessed the tool of Letterboxd to both build awareness of a film and to engage with their audience. Local distributor Maslow Entertainment paired up with Letterboxd to send out invites for Talk to Me to users in capital cities, ensuring that there was a steady word-of-mouth build up prior to its national release. Talk to Me ended up with a domestic return of $2.2 million, while in North America it became A24’s highest grossing horror film, taking in over $44 million. Naturally, this is not all thanks to Letterboxd, but it’s still mighty impressive for an Australian horror film.

Elsewhere, filmmakers actively engage with users who rate and review their films in a way that feels a little bit wholesome. The day after viewing Tim Carlier’s joyously inventive flick Paco, I bumped into the director who mentioned my review for it. Thankfully, I had left a positive rating, so it wasn’t an awkward encounter. In my chat with Nick Kozakis, I asked him about his engagement with readers who rate and review Godless, and he mentioned that he’s on there almost daily reading and responding. Letterboxd is starting to fill in the void left behind from the diminishing power of the film critics of the world.

While 2023 was the year that Aussie genre films made a comeback, it was also the year that South Australia stood tall as the state that gave space for croweaters to work their creative magic on screen. While South Australia has always been a fertile ground for great films, in 2023 the types of films coming out of the state gleefully pushed cinema to its limits, from funding body supported films like Rolf de Heer’s post-apocalyptic tale The Survival of Kindness and Kitty Green’s rural thriller The Royal Hotel, to hyper-independent productions like Bill Mousoulis’ musical My Darling in Stirling and Gabriel Bath’s experiential experimental film Ships That Bear.

The state also homed some of the very best films by First Nations filmmakers, both new and established. Travis Akbar and Derik Lynch made their film debuts with stories about identity. Travis’ powerful short Tambo shone a spotlight on the racial injustices inflicted upon First Nations soldiers who fought at Gallipoli when they returned home, it featured an impressive turn from Brenton Watts as the titular Tambo and marks the start of an exciting career in filmmaking for Travis Akbar. With the docu-drama Marungka Tjalatjunu, Derik acted as co-director, bringing the story of his life as an Indigenous queer artist to screen. For Warwick Thornton and Ivan Sen, their attention was turned towards the structural issues that face Indigenous Australians; with The New Boy, it’s the impact of religion on Aboriginal culture, and within Limbo, it’s the manner that systemic racism is embedded into the police system.

Both The New Boy and Limbo received deserved AACTA nominations, with the Aussie Oscars rightfully putting the spotlight back on Australian stories told by Australian filmmakers. Gone this year are the Hollywood productions masquerading as Australian films, allowing notably Australian stories like those seen in the diverse A Savage Christmas (Madeleine Dyer) and Streets of Colour (Ronnie S Riskalla) or the personal tales of Shayda (Noora Niasari), Sweet As (Jub Clerc), and Of an Age (Goran Stolevski) to get a moment in the spotlight.

Which leads us to the reason you clicked on this post: the Best Australian Films of 2023.

Across short films, documentaries and feature films, there were over 150 Australian films released in theatres, at festivals, or on streaming platforms. From those films, I curated a list of 56 entries which I considered for the final list. Over my years of compiling these ‘Best of’ lists, I found 2023 the hardest to pare back to thirty films. As cliché as it sounds, it pained me to leave some of the films off the list. Some of the films that missed out left me shattered (The Cost) while others moved me with their powerful central performances (Three Chords & the Truth, Emily), as some presented a slice of life that created unexpected comfort viewings (Because We Have Each Other, The Carnival)

With that in mind, here’s a nod to the films that almost made the list and deserve being sought out: Because We Have Each Other, The Big Dog, Brand Bollywood Downunder, The Carnival, The Cost, Damage, Ego: The Michael Gudinski Story, Emily, Equal the Contest, Flyways, Freedom is Beautiful, Godless: The Eastfield Exorcism, Grain of Truth, Katele (Mudskipper), Knowing the Score, Late Night with the Devil, The Longest Weekend, The Musical Mind: A Portrait in Process, ONEFOUR: Against All Odds, A Savage Christmas, Ships That Bear, Shit, Three Chords & the Truth, Violett, We Are Still Here.

Once you’ve read through this list, check out the 2022, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, and 2016 lists, and let us know in the comments what your favourite Australian films of 2023 were.

Co-directors Indianna Bell and Josiah Allen have forged a career by telling compelling character driven chamber pieces. For their first feature length film, they present an intense double handler between Jordan Cowan’s visitor in the night and Brendan Rock’s Patrick, a lone resident in an isolated caravan park. She’s off the beaten track, lost, and he’s cautiously welcoming; together they’ll put you on edge. You’ll Never Find Me uses its claustrophobia-inducing sound design to amplify the unease of the ratcheting tension between the two strangers who probe at each other like it’s a high-stakes card game. Bell and Allen excel at crafting large-feeling films on a micro-budget, leading You’ll Never Find Me to stand as an audacious feature film debut from two extremely confident filmmakers.

Listen to the interview with Indianna Bell and Josiah Allen here. You’ll Never Find Me will be available to view in 2024.

Rob Murphy’s ode to the museum of the flickering light and the people who keep it shining acts as both a tribute to his fellow projectionists as well as to the art of cinema itself. Splice Here brings forth the stories of projection booths around the world – from the remaining Cinerama screens to the Tarantino at the Sun Theatre in Yarraville to the chap running a makeshift screen in his backyard – and by doing so, reminds us why the cinema-going experience is a spiritual one. Murphy’s passion for his craft is infectious, and even though the film is two hours long, it could easily do with another hour of projectionist chatter.

Splice Here is available to buy on physical media here.

In the neo-noir Limbo, Simon Baker is Travis, a drug addicted detective tasked with visiting the fictional town of Limbo (Coober Pedy) to investigate the reopening of a missing person case. The stark, negative-like black and white cinematography suggests that any form of justice is unlikely, and this is before we discover that the missing person is an Indigenous girl. Sen solemnly condemns the cruel apathy that seethes within the white community whenever an Indigenous life is lost, and it’s within that dissemination of our national state of being that Limbo reveals the horrifying state of purgatory that we exist in; we are neither able to go back and repair the damage that has been wrought, nor is there any desire from the structurally racist institutions to heal in the present to allow for a conciliation to take place. Limbo stands as Ivan Sen’s most somber piece yet, and one of his finest at that.

Read Nadine Whitney’s review here. Limbo is available on most streaming services.

Great things happen when a documentarian is able to match the energy, mood, and style of their subject. Debut director Sean McDonald managed to do that with the never-ending whirlwind of energy, vision, creativity, passion, and soulful artist David Bromley, and together they bring forth the raucous and delightful Bromley: Light After Dark. While many may know Bromley as the accessible and prolific Aussie artist with a penchant for butterflies and beautiful women, it’s here we get to see the hard-working bloke behind the spray can. Alongside his wife Yuge, David Bromley is infectiously open about his joys and struggles, making it feel ok to share who you truly are. Bromley pairs wonderfully with Paul Goldman’s Ego: The Michael Gudinski Story.

Listen to my interview with David Bromley, Yuge, and Sean McDonald here. Bromley: Light After Dark will be available to view exclusively on DocPlay from 1 January 2024.

Director Ili Baré and writers Chelsea Watego and George Megalogenis know that to truly understand Australia, one simply needs to look at its major sporting codes, and by spotlighting one of the largest tennis events in the globe, the Australian Open, they also shine a spotlight on Australia’s treatment of refugees, racism, sexism, and climate change, amidst other things. Journalist Tracey Holmes comments that “Sport is our national love language,” and it’s with that in mind that Australia’s Open transcends being a hot button documentary and instead becomes a collective embrace and repudiation of our national identity. As with Ili Baré’s last film, The Leadership, Australia’s Open is surprisingly moving affair, all the while it maintains the thrill and energy of a close tennis match.

Read my review for Australia’s Open here. Australia’s Open will be available to view in 2024.

I usually laugh on the inside when it comes to watching comedies in public, but when I saw the pitch-black comedy Bald Future at Perth’s Revelation Film Festival, I found myself laughing hysterically out loud at the escalating abuse that boss Owen (Aunty Donna’s Mark Samual Bonanno) heaps on office worker Peter (a deadpan, mostly silent Jess Kenneally) just because he’s follically challenged. The cruelty that Owen spits (sometimes literally) is absurdly over the top and frequently nonsensical, a notion made all the more ridiculous given the noxious verbal barbs he throws at Peter at a funeral. On paper, Bald Future sounds like it might take glee in Owen’s abuse, but director Reilly Archer-Whelan and writer Michael Whyntie’s commitment to the bit and the bloody lengths they take Peter’s story make this a memorable absurdist comedy that hints at a promising filmography to come.

Read my interview with Reilly, Michael, and Jess here.

Sejon Im and Will Suen’s Sweet Juices does for dumplings what Jayden Rathsam Hüa’s Sushi Noh did for nori rolls: made you question whether you want to eat them ever again. Sweet Juices is a vomit-soaked, sweat-drenched, erotic affair where competitive black market chefs Shirong (Shirong Wu) and Tony (Anthony Roy Barton) push each other to the limits in a bid to create the very best dumpling, one that’s both an aphrodisiac and addictive. Shirong and Tony become drug dealers, of sorts, going so far as to supply the NSW Premier’s office with their illicit offerings. Like Bald Future, Sejon Im and Will Suen unapologetically dunk the audiences heads in this murky and pulpy soy sauce bath of a film, and then yak in your face as you come gasping for air. I’m loving the messy, disgusting, and downright filthy areas that Australian horror films are being pushed lately, it shows an eagerness to offend that was previously restrained. To paraphrase Vincenzo Nappi on Letterboxd, Sweet Juices puts the dump in dumplings, and for that I’m grottily grateful.

It makes complete sense that investigative journalist Allan Clarke would turn his attention to the bitter dismantling of Bruce Pascoe’s monumental book Dark Emu for his second documentary feature. The Dark Emu Story operates as a reminder of the impact and importance that Pascoe’s groundbreaking historical text had on Australian history, while equally teasing out the flaws of the culture war that erupted in the wake of its release. Clarke takes us away from words on a page and transports viewers to the Brewarrina fish traps ad Mithaka country where grinding stones have sat for centuries, and by doing so, he reminds us of the importance of the Pascoe’s research. As Pascoe sits weathered and worn in his shed, detailing the horrifying questions of his identity that he endured, we can see that all he wanted was for the nation to remember the 60,000 years of continuous connection that First Nations had with this land we call Australia.

The Dark Emu Story is available to watch on ABC iView.

Early in Hot Potato: The Story of the Wiggles, we’re presented with an unexpected sight: the World Trade Centre on fire. This moment came just as the Wiggles were about to embark on a national tour of America, and in the wake of the death and destruction, they questioned whether it was the right thing to continue with their tour. We then hear from a widower who lost her firefighter husband in the attacks. She talks about how the Wiggles music brought her a light in her moment of darkness, and how she attended a concert and met them after the show. She comments that what stood out for her about the Wiggles was their compassion and empathy. Watching Hot Potato, I was surprised by the amount of times that I found myself wiping away tears. Not because of the moments of sadness that are peppered throughout the film, but because of the immense level of compassion, empathy, and the groups complete understanding and appreciation of the need for joy in our lives. I’m almost 40 and this film has turned me into a Wiggles fan.

Read Connor Dalton’s interview with Sally Aitken here. Hot Potato: The Story of the Wiggles is available on Amazon Prime.

For me, 2023 has been a year that’s tinged by loss and grief. These are personal emotions that we often seek to internalise, especially when we are encouraged to reflect on the life someone has lived, which in turn leads us to reflect on our own lives. It was in August that I was able to view memory film and speak with Jeni Thornley about the meditative experience that she has created here. Reaching into a decades long archive of Super 8 footage, Jeni crafted a narrative of her life, of Australian films, of liberation movements, and of life on a commune, and then wrote her own personal version of a Japanese death poem, a ‘farewell film poem to life’ as you were. At its close, we are encouraged to see our own mortality as a gift, and to recognise that when we reach our death, that we should try and hold onto those moments that made us who we were, for better or for worse. Days before I spoke to Jeni, my grandfather passed away, leaving behind a legacy that will live inside his family, for us to share in our own versions of Japanese death poems. I believe that sometimes films and the people who make them appear when we need them the most, and for me, memory film is one such experience.

Read my interview with Jeni Thornley here. memory film: a filmmakers diary is distributed by Antidote Films. To find out more about Jeni’s work, please visit her website here.

Larissa Behrendt’s documentary about First Nations artist and activist Richard Bell presents the global lauded artist for who he is: a rabble-rouser and a provocateur who uses the art world to highlight the inequality that Indigenous Australians face. Released around the fiftieth anniversary of the establishment of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra, You Can Go Now! shows Bell’s own travelling Aboriginal Embassy, dubbed Bell’s Embassy, which he tours to Moscow, New York, the Netherlands, and more, where it operates as a speaking place for Bell and others to freely explore ideas and stories of activism. Bell knows this stuff can be heavy, with Behrendt meeting him on his level to create a cheeky and playfulness. You Can Go Now! is as much a history lesson as it is a celebration of Bell is a creative figure in Australia, closing with a barrage of layered statements from each of the figures in the film encouraging you to decolonise your mind and the way you live your life, no matter where you are in the world.

Read my review of You Can Go Now! here. You Can Go Now! is available on all good streaming platforms.

To paraphrase a line directly from Sam Odlum’s endearing time travelling addict comedy, Time Addicts is a fairy tale for cunts. Playing out like the filthy cousin to the Philippou brothers Talk to Me; Time Addicts is earnestly and unapologetically Australian, and championing mad dogs and derros in affectionate manner. Here, Freya Tingley plays Denise, best mate to dropkick Charles Grounds’ Johnny. Together, they’re tasked with nicking a duffle bag of stuff from a rundown house. Naturally, their meth-head minds can’t help themselves, and they simply have to test the product: a pink rock that whiffs them across time and drops them in a completely different year. Odlum’s script never excuses or condemns his characters for their drug addict ways, instead leaning into the raw charisma that both Freya Tingley and Charles Grounds exude, which in turn gives way to a surprising level of charm and emotionality. As a debut flick, Time Addicts is the surprise film of the year, subverting genre expectations in a distinctly Aussie manner and laying the groundwork to become a possible cult classic on the rise.

Time Addicts is released by Umbrella Entertainment and will be available to view at home in 2024.

Annelise Hickey’s debut film Hafekasi (translation: half-caste) is crafted with auto-biographical elements that strengthen the emotionality of the narrative of a 10-year-old Tongan-Australian girl, Mona (a phenomenal performance from Izabelle Tokava), who grows to realise that she’s different from her single, white mum (the always great Laura Gordon). Set in the suburbs of Melbourne in the 1990s, Hafekasi sees Mona trying to find her place in the world, all the while her mother attempts to understand the different life-path that her daughter lives. Hafekasi is a film full of compassion for the complicated moments we go through as we grow up, ultimately creating the sense that Annelise is writing a letter to her younger self to say ‘it’s going to be ok, you will get through this’. Annelise Hickey deservedly won the Award for Emerging Australian Filmmaker at MIFF, alongside winning the Best Narrative Short at Tribeca. With or without these awards, Hafekasi is a tender introduction to an exciting new voice in Australian filmmaking.

Follow the Hafekasi Instagram page for updates on where you can view this short film.

This is Going to Be Big is the other John Farnham documentary of 2023, with Thomas Charles Hyland’s cheeky and charming flick taking us into the process of establishing a school musical featuring Johno’s music. What on paper sounds insufferable turns into a wholesome flick as we meet the students of Bullengarook campus of the Sunbury and Macedon Ranges Specialist School, each of whom are neurodivergent teens who have their own hopes and dreams about being in the school musical. Hyland acts as a fly on the wall, presenting each student in an honest and uncritical manner, which in turn gives way to stories of teens who have been raised to find love for themselves and to embrace their own identity completely. It’s rare that we get a film that’s so sincere, pure, funny, and – as cringeworthy as this word may be – inspirational as this.

Read my interview with Thomas Charles Hyland here. This is Going to Be Big will be available to view in 2024.

It’s always a good sign when there’s a new Warwick Thornton film in the world. Here, Warwick creates a gentle poem of a film that is inspired by his boarding school days. Thornton plays with magical realism here as he weaves a story of a stolen Indigenous boy (the mostly silent, completely engaging Aswan Reid) who is whisked away in the night to a monastery run by Sister Eileen (a subdued by no less impressive turn from Cate Blanchett), a nun with more than a few secrets up her sleeve. Here, religion is in his spotlight, with Thornton imbuing his text with iconography that carries a dual meaning for Indigenous culture as it does in religion: dust swallows the sky, snakes appear as mice flood the sheds. The New Boy plays out like a memory gleamed from the back of the mind; it’s lighter than Thornton’s previous fare, but maintains the exploration of the impacts of colonisation on Indigenous Australia. By its close, you’ll be grateful once more that Australia’s finest working filmmaker has yet another film to his name. May he never stop.

The New Boy is available on physical media and streaming services.

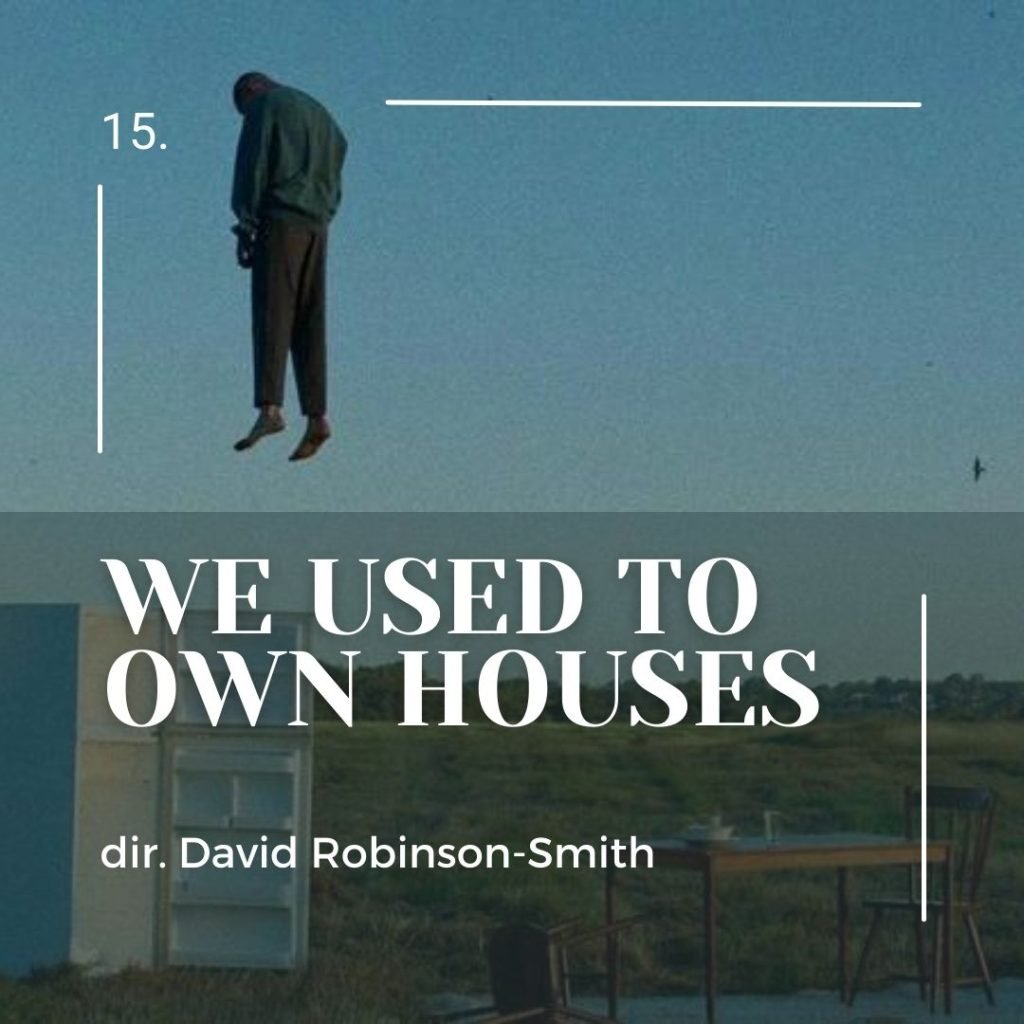

Over the span of six minutes, filmmaker David Robinson Smith (DRS) reminds us why the short film format is as valid a form of storytelling as feature length films. The desolate words of Alasdair Dunn’s poem pair with an urgent score by Wolf & Cub that meet Jaclyn Paterson’s haunting cinematography that pushes We Used to Own Houses into the grey area of our housing crisis. Thom (Thom Green) confronts Ben (Anthony Phelan), and as the two speak in verses, DRS takes us into the world and presents the all-smothering, all-diminishing reality that comes with knowing that you will never be able to own a house. We’re shown people living without walls – smoking in their cars to keep warm, sleeping in fields with a chair, a fridge, a bed, that now serve no purpose. A house is a home, a home is where you soul is, where lives can be lived. Ben says, ‘When you can’t see the stars, you stop dreaming of space;’ within the space of six minutes, We Used to Own Houses reminds us of the desolate end state of the housing crisis: a nation without dreamers or hope; a nation of soulless, empty vessels with nothing to tether them to this land.

Read more about We Used to Own Houses here.

Somewhere along the way Australian filmmakers forgot how to make films for teenage audiences. Thankfully, Jub Clerc’s Sweet As arrives to buck the trend. Shantae Barnes-Cowan takes lead duties here as Murra, a teen girl on the brink of heading in the wrong direction. Her police officer uncle (Mark Coles Smith) steps in and shuffles her off to a photo-safari with other at-risk kids. What cements Sweet As as a gem of a film is the authenticity that Jub Clerc puts into her storytelling. She recognises the difficulties of growing up, but never in a patronising way; she winks at the cheeky crushes you have, nudging at the awkward chats as you both try and figure out how to see if the other is interested. And she knows just how hard it can be to have a genuine conversation with an adult as a teenager, especially about things that sit in the darkest spaces of your mind. Jub Clerc is the first Indigenous person to direct a feature length film in Western Australia, please let her be the start of a new wave of First Nations storytellers in this state.

We need it. Sweet As is available on physical media and on streaming services.

Our Ghostly Crew follows creative couple Donna McRae and Michale Vale as they enter their second Covid lockdown in Melbourne. As a painter (a ‘solo artist’, if you will), Michael was able to sequester himself into his studio to paint a family portrait. With no suitable camera equipment, and in need of a distraction, Donna picked up her iPhone 7 and started shooting his process. What unfurls over the 22-minute runtime is the creation of a family portrait, interweaved with the conversations that flow between partners checking in on the others day, while the creative part of their psyche engages in discussions about their artistic process. Michael’s is an insular one, locking himself away in a room with the Dirty Three playing in the background to allow the painting to flow out of him, but Donna’s presence with a camera leads to questions about his creative flow. In one moment, as the face of Donna starts to emerge on the canvas, she says to Michael, ‘That’s not me.’ His silence says, ‘The painting is not finished yet. You will appear when the brush wishes you to.’ Later, when Donna goes to knock on his door and film his day, he peers through the gap to say not today. Donna then places their Schipperke Pancho on the ground, and the two take in the harmony of nature. The resulting portrait (of which the film is named after) has the two standing in a post-apocalyptic world, with madness lingering behind them as Donna cradles Pancho. Our Ghostly Crew is a moving celebration and ode to creativity. At the films close, we find that Pancho has left us, and with that motion in mind, I’m even more grateful that this film exists. When Michael is gone, this portrait will tell us who he is as a person and an artist, and who Pancho was as a dog. When Donna is gone, her films will remind us of her enduring curiosity of the world around her. When I am gone, hopefully my words will guide readers to films like Our Ghostly Crew.

At the core of director Matt Vesely and writer Lucy Campbell’s feature debut Monolith is a narrative that’s so compelling and engaging that you can’t help but get swept along by its eerie force. Lily Sullivan commands the screen as an out-of-work journalist who turns to the world of podcasting to investigate a mystery that’s fallen in her lap: black bricks have started appearing in peoples lives without explanation of where they came from or how they got there. Monolith relishes in immersing the audience into a quagmire of tension as it follows Sullivan’s interviewer down the foggy path of this sci-fi mystery. There’s more than a tinge of The X Files and Black Mirror at work here, and it’s thanks to the strength of everyone involved (a special shout out to Michael Tessari’s otherworldly cinematography) that Monolith that it never feels derivative; in fact, repeat viewings highlight how intricate the narrative is, with late reveals becoming even more unsettling when you know where it’s heading. As I mentioned at the start of this piece, Australian cinema embraced genre filmmaking in new, exciting ways in 2023, and after a run of sci-fi shorts, Matt Vesely has confidently made his name as a genre filmmaker to keep an eye on.

Read my review of Monolith here, Nadine’s interview with Lily Sullivan here, and listen to my interview with Matt Vesely here. Monolith is available on physical media and on streaming services.

In talking with director Marion Pilowsky about her splendid documentary Isla’s Way, she mentioned that most funding bodies wouldn’t be interested in funding a film about an 87-year-old woman from the middle of nowhere, but I’m beyond grateful that her film exists to show that there is an appetite for films about people whose stories we would never hear otherwise. Isla isn’t a lesbian. She’s not a lezzo. She’s not a dyke. She’s just Isla Roberts. She lives with her ‘friend’ Susan and throughout the course of the film we hear their stories. Isla is persistent and resilient, living for her country and the ponies she rides with. She’s shaped by the land and the land has shaped her soul and world view. There’s a matter-of-fact perspective on life and living that comes from Isla that, to me at least, is the purest representation of what being Australian actually is: it’s going with the flow, embracing the lives of others, and supporting those in need. We need more stories like Isla’s in the world. As the tagline says, you’ll never forget meeting Isla.

Listen to my interview with Marion Pilowsky here. Isla’s Way will hopefully be available to view in 2024.

Like every good enigma, Alena Lodkina’s second feature Petrol invites, encourages, and embraces continued interrogation and investigation. Petrol is a playful film that follows Nathalie Morris’ Eva, an Australian-Russian filmmaker who becomes enchanted by Hannah Lynch’s Mia, an almost Cheshire Cat like figure who sways in and out of Eva’s life, almost at the click of her fingers. Lodkina teases the audience as she moves Petrol from magical realism to drama to comedy to romance, often in the space of one scene. Where Lodkina’s first film Strange Colours intimately addressed the sense of isolation that can easily be found in the outback, her shift into varied genre-stylings comes with a level of confidence that is supported by Michael Latham’s sumptuous cinematography and the sound design by Steve Bond and Livia Ruzic. Additionally, while Lodkina and her creative siblings James Vaughan (Friends and Strangers) and David Easteal (The Plains) may be more widely appreciated overseas than at home (see Richard Brody’s review of Petrol for example), it’s comforting to see that a truly Australian arthouse movement is underway which is establishing a modern cultural identity on screen. In years to come, once these filmmakers have a built their bodies of work further, we’ll be grateful that they forged ahead either in spite of the system as independent filmmakers, or on the fringes of the funding bodies, making work that is distinctly their own.

Read my interviews with Alena Lodkina here and here. Petrol is available to watch on SBS On Demand.

For his second feature, Goran Stolevski turns inwards, pulling from the personal to create characters that resonate with the understanding and acceptance of what it means to be a gay man in Australia. Kol (a captivating Elias Anton) is yet to realise his queer identity, but when he meets his dancing partners brother, Adam (Thom Green), he feels the emotional cogs slipping into place: desire, yearning, affection, and the embrace of another man. Of an Age is split into two significant moments in time, divided by a volcano eruption and years of longing. By splitting the film into these two time periods, Stolevski gives us the weight of a passionate heart that’s strained by the desire for the one you love. Matthew Chuang’s intimate cinematography creates a conversation between Annelise Hickey’s Hafekasi (which he lensed) and Of an Age; both present aspects of 1990s Australia that were threatened to be lost to time. Both explore the stories of people seeking to make sense of their place in the world; stories that – if told in the Nineties – would have been directed by outsiders looking in. What makes Of an Age (and by extension, Hafekasi) resonate so strongly is how deeply informed and understanding Stolevski is of the lives that both Kol and Adam live. The strength of a beating heart resonates strong with him.

Read Nadine Whitney’s review of Of an Age here. Of an Age is available on physical media and on streaming services

While a sizeable chunk of Australian cinema focuses on the modern Aussie battler, few filmmakers have realised their stories with as much authenticity and humanity as indie powerhouse Heath Davis. Christmess is his finest film yet, with Heath giving regular collaborator Steve Le Marquand the space to give the performance of his career as a washed-up alcoholic actor trying to get his life straight at Christmastime. Christmess is so completely earnest and sincere that its seasonal flourishes (character names include Chris, Nick, and Joy) add to the warmth of the narrative rather than call attention to themselves, which in turn amplifies the respect and care that Heath has for those who are doing it tough. Christmess never wallows in the expected drama of a tale about recovering alcoholics and addicts, skewing away from the pitiful pandering that is often found in these kinds of stories to focus on the thing that matters most: the humanity within us all. Christmess has instantly become an Aussie Christmas classic, with audiences across the nation embracing it completely.

Read Nadine Whitney’s excellent review of Christmess here, and listen to my interview with Heath Davis here. Christmess is available on select streaming platforms now.

Co-directors Jack Clark and Jim Weir have made their presence well and truly known with their feature debut Birdeater. Operating in the enduring guttural resonance of Wake in Fright, Birdeater follows a group of friends as they embark on a bachelor party that immediately swerves into an extended anxiety attack full of noxious masculinity and stifling acts of gaslighting. Clark and Weir instantly put the audience on edge as they employ the razor-sharp editing by Ben Anderson, creating the sense that violence and danger could erupt at any moment. Roger Stonehouse’s cinematography amplifies the vibrancy of the rural home that the party takes place at, heightening the precarious feeling that comes from the recently flooded fields. The frenzied state that washes over the men when they are bathed in beer, hard liquor, and drugs shows that while they’re a long way from the dusty nothing of the outback in Wake in Fright, these modern men are not too dissimilar from the blokes of yesteryear. All of this tension is amplified even further by the doom-jazz score by Andreas Dominguez. Made for a song outside of the traditional funding system, Birdeater sits alongside David Robinson-Smith’s Mud Crab and George-Alex Nagle’s Mate as a powerful deconstruction and condemnation of the modern Aussie man. When the credits start rolling and your stomach starts untwisting itself, you’ll no doubt be left with the same thought I had upon my first, second, and third viewing: Burn it all down. All of it.

Read Nadine Whitney’s review of Birdeater here, and listen to my interview with Jack Clark and Jim Weir here. Birdeater will hopefully be available to view in 2024.

‘Welcome to a world without sunlight, soil or shit.’ So goes the tagline for co-directors Joseph London and Kenta McGrath’s wholly original and deeply bizarre documentary Sunlight: YES, an examination (of sorts) of bio-artists Symbiotica and their Fremantle based exhibition ‘Sunlight, Soil & Shit (De)Cycle’ which was held in 2022. The concept of the exhibition is probably best left to Symbiotica themselves: “Sunlight, Soil and Shit (the 3 S’s) are the three elements our technological utopian future farming is trying to live without. “AgTech” (precision-agriculture intelligence) aims to automate and control food production, while non-standardised elements such as sunlight, soil and shit are removed in favour of artificial light, substrates and fertilizers.” And look, if that all sounds a little bit too scientific and impenetrable, then let me tell you, that’s part of the point of the 3 S’s, and it’s something that London and McGrath lean into with their wickedly hilarious film. Static shots of a room are paired with redundant, useless data that flits on the screen. The use of an AI narrator, AMY, both examines and critiques the world of bioscience, and in doing so, they amplify the inherent absurdity of Symbiotica’s exhibition (which in turn is the point of the exhibition itself): we do so much work to be ‘green’ and ‘clean’, and the end-product is a dwindling, malnourished herb garden. At its close, you’ll quite likely feel just like Kenta McGrath did when he finished the film: completely in the dark about what you’ve just experienced, but that’s also kind of the point. Sunlight: YES encourages you to laugh awkwardly and to not know why you’re laughing at all. If and when Sunlight: YES circulates near your existence in the future, make it a priority to seek it out. I can guarantee you’re never going to forget this film, even if it’s so in ten years’ time you find yourself waking in the early morning hours to say, ‘What’s all that about then?’

Read more about Sunlight: YES here.

The symbiotic relationship between one man and the Tasmanian landscape is tenderly explored in Rachel Antony and Laurence Billiet’s expansive documentary The Giants. It’s a title that carries a dual meaning: the 6’3” man at the centre of its narrative, environmentalist Bob Brown, and the overwhelming stature of the gargantuan eucalypts of the Tarkine rainforest in Tasmania, some reaching the heights of over 100m. Both are giants in their own worlds, and as their continued existence stretches through time, communities and cultures are formed that in turn foster their own ecosystems and communities. Told with a level of admiration and awe for the world around us, and a deep sense of concern for the unfurling environmental crisis we face, The Giants acts with an apolitical urgency that reminds us how valuable and important it is that we nurture and maintain the natural ecosystem that we live alongside. The Giants is a film that I’ve found myself returning to in my mind as I live my life; the trees that I walk past on my way to work have become acquaintances, the birds that call them home have become friends, and the sounds they make when nature moves through its seasons have become the soundtrack to my life. Each time I feel these senses, I am reminded of the magnificent trees of the Tarkine and of Bob Brown’s legacy. As I mentioned in my review, “in a world of chaos and uncertainty, be a Bob Brown.”

Read Nadine Whitney’s review of The Giants here, and my review here. Read my interview with Rachel Antony and Laurence Billiet here. The Giants is available on physical media, DocPlay, and other streaming services.

Zar Amir Ebrahimi is Shayda, an Iranian woman living in Australia with her daughter Mona (Selina Zahednia), together they find refuge in a woman’s shelter away from Shayda’s abusive husband Hossein (Osamah Sami). The threat of Shayda losing Mona is ever-present, with the possibility of violence or abuse lingering outside of the frame of the camera, but it’s not the focal point of Shayda for feature debut filmmaker Noora Niasari. Importantly, this gentle film is an ode to mother-daughter relationships in times of need and desperation, and as such, Noora ensures to give Shayda and Mona enough moments of reprieve and salvation with one another to remind them of the joy and hope they need to hold onto. Echoes of Beck Cole’s stunning Here I Am play out in a scene where the women and children of the refuge dance together to an Iranian song, each getting a chance to experience a moment of joy with one another. Sherwin Akbarzadeh’s documentary-like cinematography immerses us into Shayda’s world, amplifying Noora’s deeply personal story, and ultimately acting as an invitation to also share a dance with these beautifully realised characters.

Read my interview with Sherwin Akbarzadeh here. Shayda will be available on streaming services in 2024.

Manuel Ashman is Manny, a sound recorder on a movie set who engages in one of the greatest sins of a sound guy: he loses a microphone when an actress walks away with it still clipped to her. With a boom mic in hand and headphones strapped to his head, Manny embarks on a journey across Adelaide to find his wayward mic, and in doing so, encounters all manner of unexpected artistic endeavours: music videos, time travellers, theatre sports and improv, amongst many other delights. The basic concept of Paco hides its greatest asset: unbridled enthusiasm for creative spirits and energy around the world. This gloriously good charmfest of a film is one of the most unexpected delights of 2023, with the wholesome vision of Tim Carlier coming to life in a truly beautiful and brilliant way. Carlier acts as director, writer, producer, editor, and cinematographer, and by doing so, he has cracked open his spectacular mind and invited everyone in to witness the wonderful things he can envision. Paco closes with a procession of musicians, singers, dancers, and artists triumphantly expressing themselves as one. It’s the purest thing I’ve seen in an Australian film in a long time and has acted as a touchstone of salvation for my weathered mind throughout this difficult year. It’s no surprise that many of the films on this list hail from Adelaide given the burgeoning film community that takes place there (thanks in part to the kickstart by newcomers moviejuice), but it breaks my heart a little to know that Tim has jetted off to the UK to build a career there. If the Australian film industry encouraged, supported, and amplified films like Paco, it would be much richer and better for it.

Listen to my interview with Tim Carlier here, and read excerpts from the interview that moviejuice’s Shea did with Tim for the limited edition Carlier on Carlier here

If there’s a commonality between many of the films on this list, it’s in the way that dancing emerges as an extension of the personalities of those we see on screen. For Yankunytjatjara artist Derik Lynch (co-director and the focus of this film), when he dances for his family and friends in the spotlights of car in a stunning gold dress, echoing the power and strength of Tina Turner, it’s a moment of liberation and a powerful expression of self. Marungka Tjalatjunu (Dipped in Black) deservedly won the Silver Bear Jury Prize (Short Film) and Teddy queer short film prize at the 2023 Berlinale, and in doing so, it shone a global spotlight on Inma, a traditional form of storytelling from the Anangu community which uses visual, verbal, and physical communication to pass along Anangu Tjukurpa (myths) between generations. Derik’s dance doesn’t exist in solitude, as Marungka Tjalatjunu frames his narrative in the events that have led to this moment taking place: moments of despair, connection with country, abusive and racist white folks; so that when we reach that pivotal dance, we feel the emotional exhalation of the darkness that drifts away from Derik as he moves in the light. With the support of co-director and producer Matthew Thorne and co-producer Patrick Graham, Derik’s story is committed to film, and in turn, he becomes a myth, a legend, a leader.

Read my interview with Derik Lynch, Matthew Thorne, and Patrick Graham here.

Talk to Me is a nasty flick that leans into its zeitgeist grabbing concept of teens using a ceramic hand to commune with and become possessed by the dead. Danny and Michael Philippou have gleefully crafted a fucked-up flick that never flinches away from the brutal violence and squeamish gore that comes from the union between thrill-seeking teens meet vengeful spirits. There are no safety nets here, anything is possible. While there is an allegory of drugs and loneliness at play within Talk to Me, it’s never heavy handed (pun intended). Talk to Me champions Aussie slang and our unique dialect, becoming unapologetically Australian in the process, and globally embraced for it. We’re a long way from Mad Max being slathered with a seppo soundtrack; welcome to the 2020s: the age of Bluey, Heartbreak High, and Talk to Me is here. From dunnies to durries, the rest of the world is now speaking our language and it’s all the better for it. Within its proud Australiana, Talk to Me stands as a new benchmark for horror films. Given the enduring success of Talk to Me and its genre-siblings, one can hope that Australia is about to enter a welcome era of genre storytelling. The Philippou brothers have set a challenge: Australian filmmakers, now is your time to step up, meet it, and make your mark.

Read Nadine Whitney’s review here, and my review here. Listen to my chat with Danny and Michael Philippou here. Talk to Me is available on physical media and streaming services.

[i]Screen Australia favours a blanket use of the term ‘Drama’ to refer to all films it supports, but as their genre breakdown shows, the extremely broad genre term ‘Drama’ makes up some 34% of the films produced in Australia, with globally popular genres like Horror and Sci-Fi making up 6% and 3% respectivelyhttps://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/fact-finders/production-trends/australian-features/genres